Difference between revisions of "Hot water cylinders"

m (→Types of cylinder) |

m (→Inherent risks and mitigation) |

||

| Line 183: | Line 183: | ||

[[File:Cu_cylinders_-_As_processors.png]] | [[File:Cu_cylinders_-_As_processors.png]] | ||

| − | The other three risks all relate to lack of liquid in the vessel. These can be protected against by using either a [[pressure switch]] or [[float switch]] to control when the immersion element can switched on. | + | The other three risks all relate to lack of liquid in the vessel. These can be protected against by using either a [[pressure switch]] or [[float switch]] to control when the immersion element can be switched on. |

[[File:Cu_cylinders_-_Level_switches.png]] | [[File:Cu_cylinders_-_Level_switches.png]] | ||

Revision as of 01:16, 28 November 2011

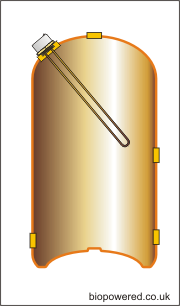

Hot water cylinders are often used to make biodiesel processors. They come with several threaded ports and usually an immersion element. These cylinders are inverted, providing a dome for draining at the bottom, as well as correct placement of the immersion element in relation to the liquid.

Contents

Types of cylinder

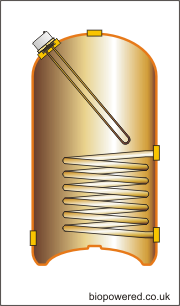

Direct cylinders are the best choice, followed by indirect - the only disadvantage of indirect is that the coil occupies some of the cylinder's volume.

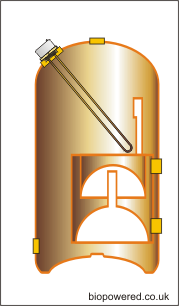

The comparatively rare "primatic" (self priming) cylinders are unsuitable for use as biodiesel processors; a much larger volume is wasted by the primatic apperatus, and not all of the liquid can be drained out. A primatic cylinder can be identified by look into the side ports - if a wall of copper is visible just inside a port, then the cylinder is primatic. If the port forms a tube that bends away to one side, then the cylinder is indirect and you're looking into the end of the coil. Another quick check is to jiggle the cylinder - if there is a coil this can be felt wobbling around inside.

Hot water cylinder standard sizes

| Standard Cylinders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British standard |

External diameter of cylinder (excluding insulation) |

External height over dome |

Min storage capacity | Expected port fittings | |

| Direct | Indirect | ||||

| mm | mm | Litres | Litres | female, BSP | |

| 0 | 300 | 1600 | 98 | 96 | 1" |

| 1 | 350 | 900 | 74 | 72 | 1" |

| 2 | 400 | 900 | 98 | 96 | 1" |

| 3 | 400 | 1050 | 116 | 114 | 1" |

| 4 | 450 | 675 | 86 | 84 | 1" |

| 5 | 450 | 750 | 98 | 95 | 1" |

| 6 | 450 | 825 | 109 | 106 | 1" |

| 7 | 450 | 900 | 120 | 117 | 1" |

| 8 | 450 | 1050 | 144 | 140 | 1 1/4" |

| 9 | 450 | 1200 | 166 | 162 | 1 1/4" |

| 9e | 450 | 1500 | 210 | 206 | 1 1/4" |

| 10 | 500 | 1200 | 200 | 190 | 1 1/2" |

| 11 | 500 | 1500 | 255 | 245 | 1 1/2" |

| 12 | 600 | 1200 | 290 | 280 | 2" |

| 13 | 600 | 1500 | 370 | 360 | 2" |

| 14 | 600 | 1800 | 450 | 440 | 2" |

Inherent risks and mitigation

Any processor with an immersion element directly heating the liquid presents a possible risk of fire or explosion. Incidents reported with the use of copper cylinders include:

- the element accidentally being turned on with the cylinder empty, but full of explosive vapour (NEVER put the element on a 24h timer as it may come on again the next day!)

- the element not being turned off when the cylinder is drained

- the liquid level dropping because of a leak, exposing the element

- the element not being completely covered by the liquid because the element is too long

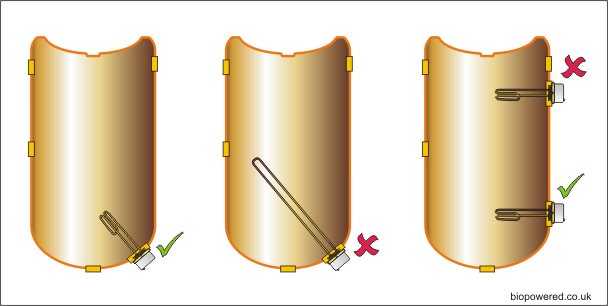

The last of these is easily avoided; before being used as a processor, the heating element should be removed to determine its length. Unless the cylinder is particularly tall, long elements are not suitable, as the tip of the element may protrude above the surface of the oil and Methanol mix, igniting any Methanol vapour present. For this reason, long elements should be replaced with the folded 11" type.

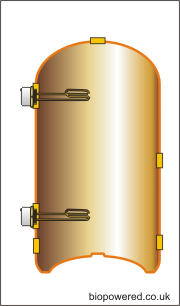

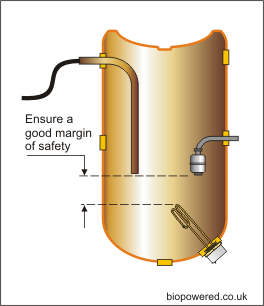

The other three risks all relate to lack of liquid in the vessel. These can be protected against by using either a pressure switch or float switch to control when the immersion element can be switched on.

Copper as a catalyst to oxidisation

Unfortunately, copper acts as a catalyst to oxidisation of biodiesel - even at the level of a few parts per million in the fuel. Fortunately, this only really applies to long term storage, and as the average homebrewer is likely to use their fuel within a couple of months of production, this does not cause any problems. It is, however, advisable to avoid storing your fuel in the copper cylinder if possible.